Conditional Optimism

In the summer of 2016, I discussed an important paper by Martin Stuermer and Gregor Schwerhoff at an academic meeting and wrote up a blog post that summarized the key points from my discussion. In light of decision to award a Nobel prize in economics for work on climate change and endogenous technological progress, I thought it would be helpful to go back to the issues I discussed there. In particular, I thought it might be useful to restate my stance of “conditional optimism,” a term that has resonated for many. As I wrote back then:

Complacent optimism is the feeling of a child waiting for presents. Conditional optimism is the feeling of a child who is thinking about building a treehouse. “If I get some wood and nails and persuade some other kids to help do the work, we can end up with something really cool.”

The content here is presented in my new blog format, but is drawn from something I posted back in 2016.

Last Friday at the NBER Summer Institute, Martin Stuermer presented a thought provoking paper (written jointly with Gregor Schwerhoff. Note: This link now points to an updated version of the paper that the authors circulated in Oct. 2018.) It takes an important and puzzling fact seriously, then uses some credible theory to work out the implications of the fact. In the discussion afterwards, a challenge to the paper’s apparent optimism yielded an insight that might have practical implications for ongoing policy debates. It was a wonderful illustration of how science works.

The practical insight is that there are two very different types of optimism. Complacent optimism is the feeling of a child waiting for presents. Conditional optimism is the feeling of a child who is thinking about building a treehouse. “If I get some wood and nails and persuade some other kids to help do the work, we can end up with something really cool.”

What the theory of endogenous technological progress supports is conditional optimism, not complacent optimism. Instead of suggesting that we can relax because policy choices don’t matter, it suggests to the contrary that policy choices are even more important than traditional theory suggests.

Two Centuries of Progress

The fact that sets things in motion for Stuermer and Schwerhoff is captured by this plot of resource prices over the last two centuries. Over this period, the quantities of resources extracted each year increased by 2 or 3 orders of magnitude, but prices show no long-run tendency to increase:

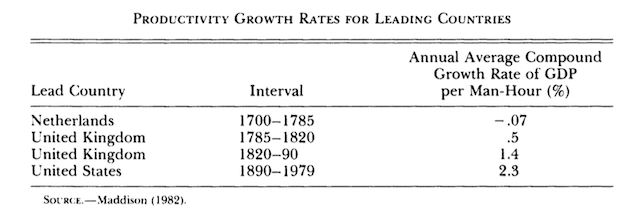

This is the price-dual to the evidence on output quantities that first motivated me to rethink the theory of growth. See for example, table 1 from my 1986 JPE paper:

The underlying theoretical question that both types of evidence pose is not simply why progress is possible in a world of scarce resources. The real question is why progress comes so easily that it seems to be free, like gifts from Santa. The point of the theoretical models is that there is a big difference between “seems to be free” and “is free.”

In the discussion last Friday, someone questioned the optimism of the Stuermer-Schwerhoff analysis: “How can we reconcile these results with a realistic assessment of the very real risk we now face of harmful climate change?”

I agree with the premise behind this question. By emitting carbon dioxide when we burn carbon-based fuel (and by emitting other greenhouse gases too), humans are changing our natural environment in ways that could be very harmful. Faced with such risks, I also agree that complacency is dangerous. But there is no logical connection between optimism and complacency.

The conclusion from endogenous growth theory is that progress is not free. We make progress because of things that people do. This is what it means for technological progress to be endogenous. The models and evidence suggest that the benefits we get when people do the things that produce progress are so large, and the resources that it takes to produce the progress we’ve enjoyed are so small, that the progress seems to be free. This means that we should encourage people to do a lot more of whatever it is that they are doing to generate progress. Instead of encouraging us to be complacent, the theory encourages us to be even more active.

The additional insight from the Stuermer-Schwerhoff paper is that bad policy can lead not just to under-investment in beneficial types of technological change. Bad policy can also lead to over-investment in harmful types of technological change. For fossil fuels, the magnitude of the potential harm could be extremely large.

The reason for this surfaces naturally when you look at their data on resource prices. Fossil fuels present us with a classic “second best” problem. In a first-best world, it is good when innovators come up with ways to produce things that people want at lower cost. But in our second best world, with a market price for fossil fuel that is too low (because the market imposes no charge for emitting greenhouse gases), it is bad when innovators come up with ways to extract fossil fuel at lower cost.

The textbook analysis of externalities and pollution suggests that the solution is to get a once-and-done increase in the price of fossil fuel by imposing a steep tax. The historically informed dynamic analysis of Stuermer and Schwerhoff suggests a different policy response. The main reason to put a tax on greenhouse gases is not the one from the textbook. This is a tax that we want to people to avoid. We want innovators to discover all kinds of clever new ways to let people have the things that they want without paying this tax.

This changes how we think about the timing of the tax. We want innovators to know that the tax is coming and to take steps now to make sure that when it bites, it will be little more than a nuisance. Eventually, we want the tax to be so high that no one ever pays it, yet no one cares because it is irrelevant.

One way to achieve this would be to start with a very low tax on greenhouse gases right away and commit that the tax (in dollars per unit of greenhouse gas emitted) will increase gradually but inexorably. Innovators will start investing now in ways to for people to get what they want without paying the tax. They will stop investing in ways to extract more fossil fuels that will be subject to the tax.

After all the fear and hand-wringing, once we commit to this kind of tax, progress will continue but in a slightly different and much better direction. It will still seem to be free.

Our intuition tells us that solving this problem cannot be so easy. But intuition has also been telling us for two centuries that the price of natural resources has to climb as the rate of resource extraction increases. So what are you going to believe? Your intuition or the logic and the evidence?

The natural world revealed to us by the facts of history could have been different. It might have been the case that discovering new extraction technologies is so difficult that firms invest in these new technologies only when they are sure that the price of the resource will be higher. This is not what the facts show. People kept coming up with innovative extraction technologies even though there was no realistic prospect of higher prices. The innovation was not all that difficult, so they did it anyway.

The lesson from resource prices (and from almost every other domain where we’ve looked carefully) is that small incentives can generate lots of innovation. This means that small changes in incentives will encourage more discoveries that are truly beneficial, such as ones that give people what they want without emitting greenhouse gases. These small changes will also discourage the socially harmful discoveries that keep the price of fossil fuels too low. So, there is no basis for complacent optimism and tolerance of bad status quo policies and lots of logical and empirical justification for conditional optimism.

The essential condition is:

“If we use policies that start modestly and grow over time to create incentives that guide innovation toward discoveries that are beneficial and away from discoveries that are harmful …”

The optimistic conclusion is:

“Then we can do all the things we want to do: end extreme poverty and raise standards of living for everyone; and start reducing the harm that we are doing to the natural environment with the goal of doing no new harm, then perhaps even undoing some of the harm we have up until then.”

The Rush to Urgent Pessimism

During the 1970s, the Club of Rome famously argued that our economic system was on the verge of collapse because we were running out of fossil fuel. This analysis was flawed not simply because it got the magnitudes wrong. It got the signs wrong. The problem facing the world is not that the earth’s crust contains too little fossil fuel and that we won’t have enough innovation to solve this problem. The real problems are that the earth’s crust contains far too much fossil fuel and that too much of the type of innovation that Stuermer and Schwerhoff highlight is making this problem much worse.

I suspect that there is more to the failure of Club’s analysis than the tendency for intuition to lead us astray. In retrospect, it looks like an instance of motivated reasoning. Advocates seem to have been too eager to generate a sense of pessimistic urgency.

The motivation probably came from an implicit model of political action in which optimism encourages complacency and pessimism spurs action. There is a grain of truth to this model; optimistic complacency can take root all too easily. But if we had emphasized the conditional optimism that is consistent with the scientific results — the logic and evidence of the Stuermer-Schwerhoff analysis — we would probably have found that it is a better way to encourage the policy action.

Pessimism is more likely to foster denial, procrastination, apathy, anger, and recrimination. It is conditional optimism that brings out the best in us.

So we should stop saying that “the end is near.” We should say instead:

Ok, we made some mistakes. We can start fixing them by pointing our innovative efforts in a slightly different direction. If we do, we can do things that are even more amazing than the truly amazing things we have already accomplished. It will be so easy that looking back it will seem painless. Let’s get going.

And as a final note, I realize that there is an issue about how to coordinate policies between nations. But once the United States takes the lead, I’m willing to bet that the required coordination between nations will be a much easier challenge to manage than most people think.

Unfortunately, because of all the fear and pessimism, getting the United States to take the lead will be difficult. So the United States may be stuck for some time playing the absurd role of the richest kid in the neighborhood, who whines about wanting to build a treehouse but claims that there is no point even trying because it will be hard and none of the other kids will join to help.

For me, the key insight from the discussion spurred by the Stuermer and Schwerhoff paper is that in response to this kind of collective learned helplessness, it probably doesn’t make sense to prescribe another dose of pessimism. It would probably be better if somebody turned off the television and told this kid to go outside and build something.