Looting, Silicon Valley Edition

The lesson from the 1980s that everyone seems to have forgotten (or never wanted to admit), is that bank losses due to interest rate risk merely set the stage. It’s the strategies that insiders use to loot their doomed institutions that cause so much trouble.

The reaction to looting during the S&L Crisis

Back in 1993, when George Akerlof and I presented “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit”, other economists told us that “bankers wouldn’t just break the law and loot a financial institution.” It was hard to know how to respond. Our paper presented abundant evidence that bankers did in fact loot the institutions they controlled. It was rational to do so because few were ever prosecuted. William Black, with whom we worked closely, made a similar case in his book, The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One. He was equally puzzled about the disinterest expressed by economists in the evidence he presented.

Economists seem to get very attached to their theories. When they do, they have trouble complying with the cardinal rule of science–a fact beats a theory every time.

What happened at SVB

If you think that the decision makers at SVB were well-intentioned naïfs who tried to fly too high, you are in the thrall of a lovely little theory associated with the phrases “moral hazard” and “fourth quarter football.”

If that is your theory, consider this fact reported by Silla Brush, Noah Buhayar and Allyson Versprille of Bloomberg. The headline was spot on:

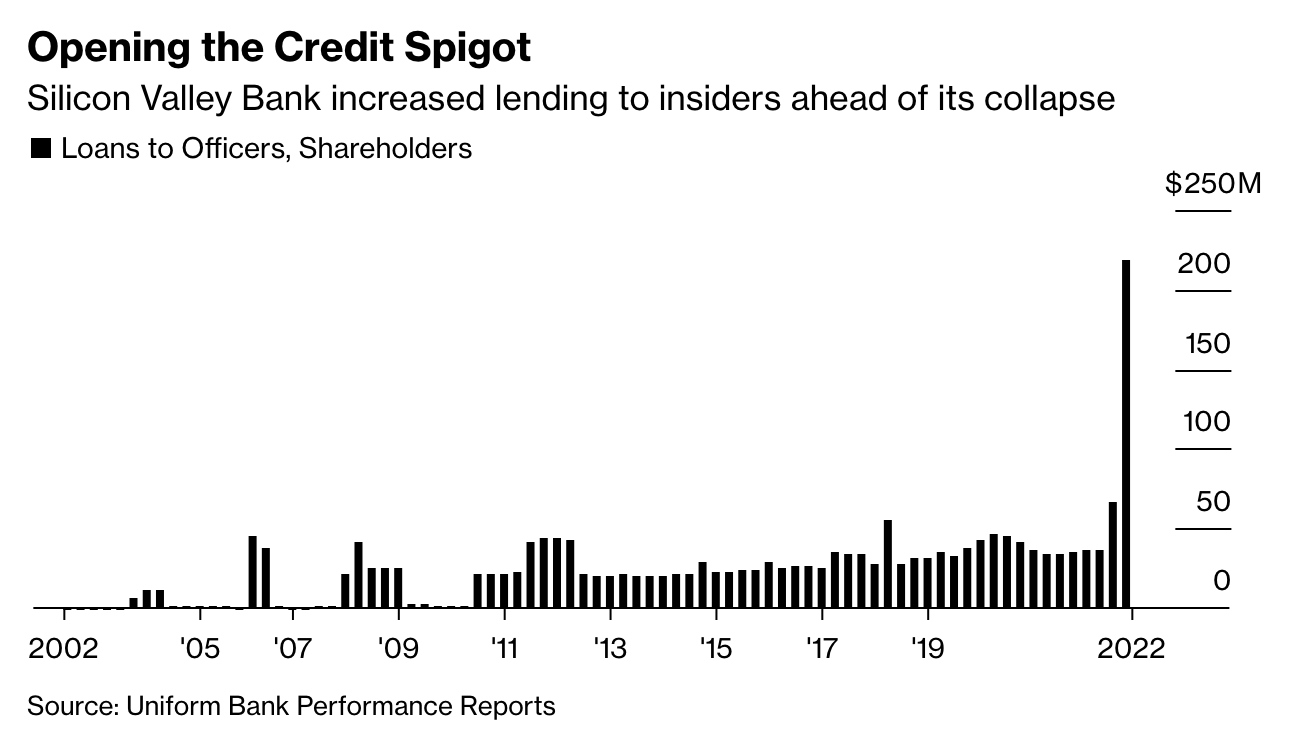

SVB’s Loans to Insiders Tripled to $219 Million Before It Failed

From the body of article:

In its most-recent proxy statement, SVB Financial Group, the parent company of Silicon Valley Bank before its collapse, said it made loans last year to related parties including “companies in which certain of our directors or their affiliated venture funds are beneficial owners of 10% or more of the equity securities of such companies.” (My emphasis. See below.)

The chart from the article showed how striking the change was in 2022:

The mechanics of looting

If insiders want to walk away with money from their bank, all they have to do is make loans to a corporate entity they control, then default. This is why I emphasized the word “companies” in the quote from the story. If you want to loot, you never want to be personally liable for repaying the loan. Which raises a question. Why don’t regulators insist that all loans to insiders include a personal guarantee?

The way things stand, lazy insiders could just lend to a corporation they control, have it pay them a huge salary, then declare bankruptcy when the loan proceeds are all gone.

To limit the risk of prosecution, most insiders are a little more creative. One version of the “Texas strategy” pioneered by real estate developers who controlled a savings and loan used the land flip. An insider at one bank would borrow and over pay for land sold by a cooperating insider at a second bank. The collaborator at the second bank would over-pay for a comparable plot sold by the first insider. By trading back and forth, they could push the price up and keep borrowing more against land that was supposedly more valuable collateral. Eventually, the insiders walked away with funds from their banks equal to the phony capital gains that they engineered on all the land sales. Their institutions were left with loans that exceeded the true value of the collateral they were left with by the same amount. It worked like a charm. Few were ever prosecuted.

Signs of looting at SVB?

So what should you look for at SVB? Collusion plus lending to corporate entities controlled by insiders. What type of collusion? Perhaps with VCs who want to goose the returns on some of their funds. (Don’t blame me. I’m not the one who suggested the verb “goose.") From Nathan Vardi at Market Watch:

Hurley, however, was not in the business of lending to companies and operating businesses. He headed SVB’s global fund banking group that funded the venture capitalists themselves with a piece of financial engineering known as fund subscription lines. These loans were used to make initial equity investments in companies and served several purposes, including goosing a key metric that made venture capital fund returns look better than they would have otherwise.

“We are probably one of the largest fund finance practices in the world … to still fly under the radar has been surreal,” Hurley said in a 2021 podcast. “This organization is just so supportive of this business and is really all-in on fund financing.”

By the way, “surreal” was a word that came up a lot in discussions of the context of the Texas land boom of the 1980s.

By the end of 2022, the bank was holding $41.3 billion of these loans on its books, making up 56% of its total book. SVB created a new business segment, global fund banking, to manage its subscription lines with Hurley in charge. By contrast, debt financing the bank extended directly to startups, tech companies and biotechs amounted to just $15.3 million, …

If you are cynical, you won’t be surprised that SVB didn’t make any money on these loans:

The subscription lines were SVB’s main business, but the problem was it was not a lucrative one. The loans generated very low returns, even compared to commercial loans, which themselves were not yielding so much due to the low-interest-rate environment.

Looking ahead

Part of the reason why no one wants to buy SVB may be that outsiders can’t establish the true value for all of these subscription lines.

Don’t be surprised if “serious people” say that they are “shocked, shocked” to discover that many of the loans in that $40 billion portfolio went to entities that can’t repay. They will probably explain it away as “forth quarter football”–taking big risks to get out of a hole–even though these loans were more like punts than Hail Mary passes.

No doubt, the VC principals who were keen on goosing returns appreciated SVB’s willingness to build up a $40 billion book of loans that offered such low returns. How could they show their appreciation? By letting SVB insiders share in their gains. Where do you suppose an SVB insider would be able to borrow enough to buy a piece of that action?

And watch for information about loans to insiders at First Republic.