The Deep Structure of Economic Growth

When I was working on growth in the 1990s, I wrote an article on the economic growth for an encyclopedia of economics. (The links here take you to a version of this article that I updated in 2016.) My goal was to provide an accessible introduction to our understanding of growth without shying away from its deep conceptual foundations.

- We can share discoveries with others.

- There are incomprehensibly many discoveries yet to be found.

The jargon for the is the "nonrivalry of knowledge;" for the second, "combinatorial explosion."

I've been pleasantly surprised about how well it seems to have served its intended purpose. Non-economists have said that it helped them understand why unlimited growth is possible in a world with finite resources. Professional colleagues have been intrigued by the discussion of combinatorial explosion its interaction with nonrivalry. Specialists and non-specialists have latched onto its discussion of meta-ideas; ideas about the discovery of ideas.

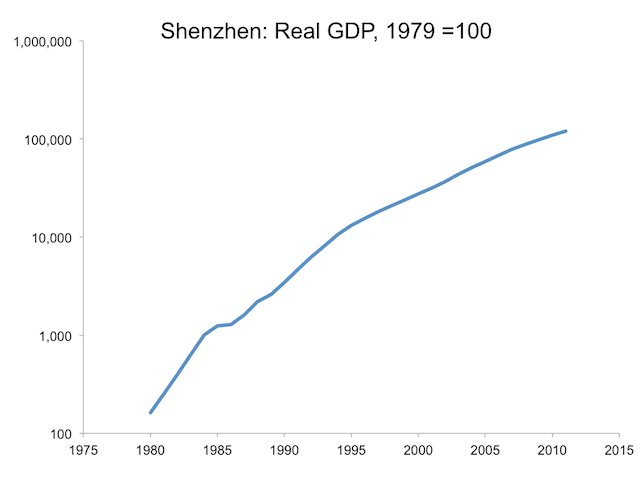

And by the way, it shows that if we treated Shenzhen as a city state analogous to Singapore, it would have the fastest rate of GDP growth ever observed. It takes sustained growth at a rate of more than 20% per year to increase output by 1000 fold in 30 years.

Martha Derthick and Policymaking for Social Security

Martha Derthick died recently at the age of 81. I never met her, but I became intimately acquainted with her book Policymaking for Social Security. I stumbled when I was collecting raw material for a paper I wanted to write to illustrate the importance of what political scientists call “expressive” voting. The book turned out to be a gold mine. It has more page markers than any other book I own.

Header Images

This page provides some background information about the header images for this website. Much of my current work pertains to urbanization. One of the small pleasures in this line of work is the chance to enjoy the visual appeal of maps. The image above shows the part of the map for the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan for New York City that includes 42nd St, running from 9th Ave on the left past 5th on the right.

Intellectual History

In the fall of 2011, I joined the Department of Economics at the NYU Stern School of Business. There I am starting a new program on the wave of urbanization that is now bringing billions of people into cities. In this century, the world’s urban population will gain more residents than in all of history to date. Because the world population will stabilize by the end of the century, humans now have a chance that we will never have again: to start dozens, perhaps even hundreds of new cities.

Where has all the excludability gone?

My previous post, which answered the question, “Why has growth has been speeding up?” made no use of the concept of excludability. So why did I make such a big deal about partial excludability in my 1990 paper? At least since Marshall handed down his Principles of Economics (arguably since Adam Smith told the story of the pin factory), economists have fretted about how to reconcile the increasing returns associated with what Smith called increases in “the extent of the market” with the obvious fact that in real economies, lots of firms of all sizes compete with each other.